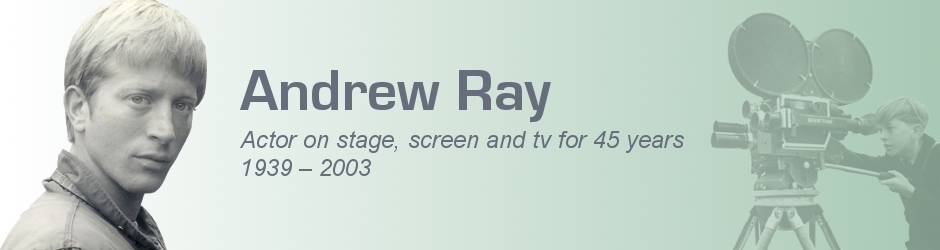

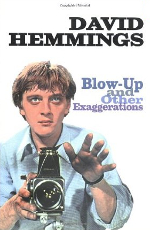

This extract is from David Hemmings’very entertaining posthumously published autobiography, Blow Up and Other Exaggerations (Robson Books) At 17, Hemmings had just got his first job in provincial rep theatre. “At a high-Victorian theatre in a large northern town, I met Andrew Ray, another young actor, who became a great friend. He was the son of a well-known comedian, Ted Ray, who had made his name before the war and since on what we used to call the wireless.”

This extract is from David Hemmings’very entertaining posthumously published autobiography, Blow Up and Other Exaggerations (Robson Books) At 17, Hemmings had just got his first job in provincial rep theatre. “At a high-Victorian theatre in a large northern town, I met Andrew Ray, another young actor, who became a great friend. He was the son of a well-known comedian, Ted Ray, who had made his name before the war and since on what we used to call the wireless.”

For eight weeks Andrew and I shared a room in the spotless semi-detached, brick and pebbledash villa of a seasoned theatrical landlady called Mrs Wainwright. Mrs Wainwright had curly white hair, small silver spectacles and wore floral pinafores of a kind I’ve only ever seen on Rupert Bear’s mother. Every day, before we headed off for the evening performance, she gave us a delicious high tea, of which she was very proud, and we were very appreciative, never leaving a scrap on our plates.

But we were both still at that stage in our lives when change and fashion were important, as much with drink as with anything else, and for some reason we were going through a sherry phase. I realise this must sound incredible now, but there was much more sherry about then. Besides, in the interests of time and motion, not to mention sheer economy, sherry gets you drunk quicker and cheaper than anything else on the market (apart from Buckfast Abbey Tonic Wine ask any Glaswegian teenager). And there are a lot of very happy old ladies in homes all over the country who will testify to the merits of good, old fashioned sherry.

We favoured a dry fino variety and made sure we always had a bottle in the wardrobe, to hide it from our landlady’s possible disapproval. After a week, however, we noticed that the sherry was going down rather fast, so naturally we blamed each other, and both denied it vigorously.

We concluded, with the steely logic of any of the mackintoshed detectives we were playing on stage, that if it wasn’t one of us, it must have been someone else. We made straight for our nearest offy and bought another bottle. We drank enough from it to accommodate a good measure of our own pee and hit it seriously.

By the end of the next week, the level in the bottle had dropped again and gleefully we told all the cast what we’d done. They howled their appreciation, and from then on all you had to do to corpse someone on the stage was to whisper as you passed them, “Sherry’s gone down again.” It was guaranteed to blast them away, and it became the season’s running gag.” Routinely, we’d buy a new bottle take some out, top it up, put it back in its hiding place and, sure enough, a week later it had gone down, and we’d pee in it again. It was astonishing to me that someone as overtly respectable as Mrs Wainwright should not only be pinching her lodgers’ booze but drinking it, and enjoying it enough to come back for more despite the fact that it was a good 50 per cent pure pee. But she was being so sweet and kind to us, I almost felt a few pangs of guilt, though not enough to stop doing it. Nevertheless the process and the jokes continued joyously for the rest of the season.

When it ended, we stood with our suitcases, saying, ’Thanks Mrs W, you’ve been absolutely wonderful and you’ve cooked some lovely meals for us.’

Just as we were getting into the taxi, she leaned through the window with her russet-apple cheeks glowing, and a tiny tear in the corner of her eye.

’Mr Hemmings, Mr Ray, you’ve been the nicest boys I’ve ever met in my life, and I’ve loved having you, so I do have one little confession to make.’

Andrew and I looked at each other, knowing what was coming.

“I’ve been going up to your wardrobe from time to time,”she went on, “and taking a bit of your sherry, but I only did it because I do know how much you love your trifle.”

We tried to cover the green tinge that must have coloured our faces as the taxi drove away, while she waved a small lace handkerchief at us. At the station we met up with the rest of the company, who were going back to London. Andrew and I looked at each other again and we shook our heads. We couldn’t tell them. They already knew that, without fail, we’d had three helpings of trifle every Friday night.

Postscript: David Hemmings died suddenly on December 3 2003 at the age of 62.